The start of the trip did little to dispel the myth that Germans can be perhaps less than friendly. After arriving at the Munich central railroad station armed with the address of the hotel where I was to meet my father, I approached two men who were leaning against a building, smoking.

“Excuse me,” I said sheepishly since it´s always awkward assuming someone speaks English when you don’t speak their language. “Could you?…” I said grasping the paper with the hotel´s street name.

“Pausa,” one of them said rather aggressively, and turned again to his colleague. I assumed this meant he was on break.

“You´re not going to tell me where the street is?” I said in amazement.

His friend, perhaps sympathizing with my consternation, pointed to a street diagonal to where we were as being the one I wanted. I found my father and we went out to eat dinner.

The central walking part of the city is delightful, full of people, cafés, bars and performers who would suddenly have to throw a tarp over themselves to protect against the continuous intermittent showers. We dined at a pleasant restaurant, looked into the beer hall where Hitler used to hang out and harangue and turned in.

Monument to those killed in Srebrenica

Checking in for the flight to Sarajevo was slightly nerve wracking since this idiot of a travel agent managed to mangle my ticket by putting my last name as Gordon. The officious woman at the counter informed me that if the computer didn´t accept my passport I would have to pay for another ticket. If venomous thoughts about somebody could kill them over a distance, my travel agent would have been a dead man. Fortunately, the computer took mercy and all was well.

We were picked up at the airport by Kasey and her son Benjamin, and on the way back the streets were lined with posters of smiling yet wretched politicians, most of which are appealing to nationalism that might once again rip the precarious country of Bosnia apart. Having settled into her apartment, we headed towards the center of town.

We walked around the old town, which is almost equally divided between what was built during the Austro-Hungarian empire and the other half when the Ottoman Empire ruled. We went to a mosque where worshippers seemed unfazed by the hordes of tourist taking pictures and selfies while they beseeched Allah for his mercy.

The museum for Srebrenica was perhaps not the most sanguine place to start a tour but it seemed almost the respectful thing to do and we would be going to that fateful spot later in the journey. Names and images of the 9000 or so victims, men and boys killed over a three-day period, lined the walls, grim documentaries are played and re-played. It is a searing reminder of the world simply turning away from those in need where revenge spawned by an event that occurred five hundred years previously once again spewed evil.

This was really an indictment of the United Nations and the museum was selling tee-shirts that said United Nothing. It essentially caved into the Serbian general who threatened the Dutch peacekeepers who basically delivered the victims into their tormentor’s hands.

One leaves these kind of museums in a kind of daze, unable to comprehend humanity´s barbarity or the insouciance of the rest of the world in a time when professing ignorance is an untenable excuse.

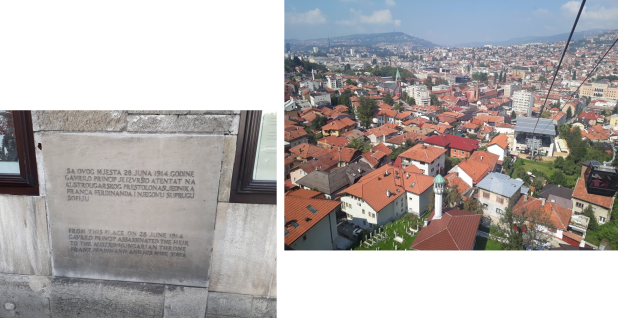

The obligatory photograph was taken on the spot where Franz Ferdinand perished, unleashing misery for millions of young men in the four-year global carnage that followed.

Kasey has several stores in Sarajevo, and many of her clients are Arabs from the gulf states, Qatar and the Saudis. Western indifference about the fate of the Bosnian Muslims created a vacuum happily filled by Muslim countries, with the Saudis funding hundreds of new mosques around the country or the Malaysians building things like shopping centers.

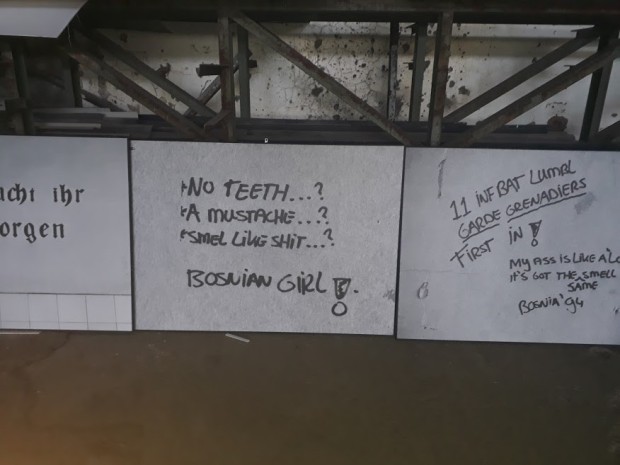

Anti-Muslim hate propaganda

Kasey told us about a new hotel/resort project spearheaded by the Saudi money was being set up just in the hills outside of Sarajevo. “No alcohol. It will be tough to get the locals to go,” said Kasey.

Dinner was traditional stuffed peppers which satisfied dad´s yearning for traditional “Yugoslav” food. Much wine was consumed (by me anyway) and Kasey and I talked about old times and people that I had long since forgotten about. We have known each other for 35 years and worked in many of the same places so memories are in abundance.

The next day we took the cable car up to one of Sarajevo´s surrounding mountains which gave us a spectacular view of the city. Benjamin and I walked down to the place where the toboggan race had taken place in the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics, now unused and full of graffiti. When I wanted to go off the path as a short cut to the toboggan track, Benjamin yanked me back and said “be careful, there could be mines.” Just one of the many reminders that just twenty-five years ago, this place was in the midst of a bloody war.

Indeed, the geography of Sarajevo and all of the rest of Bosnia that I saw was such that whoever controlled the higher ground had a huge advantage. Since the Serbs seem to have anticipated the coming war more than the Muslims, they managed to occupy much of the higher ground, to the great detriment of those stuck in the valleys. More on that later.

For lunch we went to a shevap restaurant purportedly the best in the city despite it strange location net to the railway station. There were dozens of Syrian refugees milling about, some drinking, others smoking, all with a look of blank desolation. They are being housed outside the city though many prefer to sleep rough in the city itself.

We dined in a restaurant on the road that had been lined with Serbian snipers raining bullets down on the city. Again, the complete normality of the place today contrasts to the treachery taking place in the very same spot 25 years previously.

The next day we were introduced to Nihad, who was to be our driver for the next couple of days. He was short and extremely stocky, short-cropped thinning hair, gray eyes and a wry smile. He also liked to talk, which was good since what he said was very interesting.

Nihad, like many, has glowing memories of Tito and constantly harks back to the days when everyone, from the street sweeper to general, had a decent life.

“Take my father, he worked for the same company and after 15 years, they gave him an apartment!”

“Me, I work for company for 15 years and after 15 years, all they give me was the door.”

The village of Sapna, tucked into the hills

We asked his opinion about the Serbs, rationalizing that any enmity was pretty justified given the suffering endured largely due to their perfidy and global neglect.

“I have nothing against the Serbs personally, just their leaders. My wife and I, we lived in an apartment owned by a Muslim. He treat us bad, so I say let´s go. We find another apartment, this one owned by a Serb. This man, he is like father to me.”

His family hadn’t been religious at all, with the commitment to organized aspects of faith restricted to weddings and funeral like many of their Christian brethren.

“But my grandfather one day ask me. When the last time you go to the mosque? I say I don’t remember, and my dad he hits my head, “what do you mean, we went the other day.” I know this is a lie, but I’m just a kid. When my grandfather go out, my father say, “sorry for that, I have to pretend sometimes.”

Nihad drove using his natsat, which mostly worked but got us confused around Tusla where we circled around lost for twenty minutes. We stopped to get gas and Nihad asked if he minded whether he smoked a cigarette. While puffing he lamented his habit.

“I can’t stop, no way,” he said sadly as if it might be the death of him. But for those who have seen death and suffered trauma, death by cigarettes might be a better way to go than being butchered by an ephemeral enemy.

In every town there were posters of politicians.

“With this lot,” Nihab said with derision pointing to the daughter-in-law of the former president Izbekovich, known for her graft and corruption, “sometimes I think it would have been better if the Chetniks had killed all of us.”

It is hard not to see cemeteries everywhere you go, either Muslim or Serb, with not all the dead coming from the recent conflict, but a good proportion occupying the space there.

Nihad dropped us at Ibrahim’s house in the town of Sapna, which was nestled onto a forested hill where still no one dares to go given the extensive presence of mines. He met us with his wife, a lovely and lively woman who wore a scarf, and their family of Iphram, their son, Nina and three children.

We sat outside in a covered veranda Ibrahim had built; bowls with apples, trays with three kinds of biscuits, walnuts, watermelon were thrust upon us, and being hungry and not sure whether this constituted lunch, ate merrily.

Conversation flowed between Nihad and the family, and he left with his hands piled with apples, honey and eggs. He had never met them before and this certainly gave credence to his earnest assertion, which I had considered with a hint of derision, that there was little poverty “because we all help each other.”

He would come back in two days to fetch us and I looked forward to spending more time with him.

Meanwhile, we were ushered inside for a huge lunch for which little room was left in my stomach. Being essentially a self-sacrificing sort, I managed to ingratiate myself to them eating heartily, a process that was continual throughout my time there. Their house was extremely comfortable, Ibrahim had been a builder, in fact had himself built this house and three others on the same road, of various family members who were now all working abroad.

He also praised Tito and the golden years of Yugoslavia, where he plied his trade throughout the country, and, he said proudly, was welcomed into many houses in Macedonia, Montenegro and the other four countries that make up that decomposed former country.

Communication was difficult with Ibrahim and his wife, limited to please, thank you, good, very good and I’m full. The only other words I knew were motherfucker and the like, so not necessarily useable in a pious Muslim household.

Pious in the best sense; never once was religion foisted on us or actually entered the conversation, except in the political sense of Bosnia as being Muslims or Serbs. Shortly after we arrived and were having inchoate conversations that all ended with smiles and laughter, Iphram quietly went to a chest of drawers, got a small rug and then next to the couch started praying. He was himself a man exuding calm, and as he prayed, he appeared in complete peace.

A walk was suggested and Iphram volunteered to show us around. We asked Ibrahim who declined with a chuckle. During the war, apparently, every two weeks he had walked 40 kilometers to Tusla, always having to avoid detection by marauding Serbs who would certainly have killed him, where Iphram and his siblings studied. He was done with walking.

Since mines lingered, the only real place to walk was along the main road in the valley and then up the other ridge. A Serbian town was about one hundred meters away and before crossing over a bridge, walked past a house owned by a Serbian. These people, who are ethnically the same and so look like each other, do the same professional things, eat the same food, have a shared history and still religion divides them.

Towards the end of the afternoon, we drove down through the tiny town of Sapna, up the other side of the ridge and to the farm where the family had spent the entire war trying to survive. The other side, where they now lived, had been occupied by the Serbs who were constantly targeting them with sniper fire.

Now it just seemed bucolic, existing in a kind of time warp where people live off the fortunately very fertile land. The plot had been in Ibrahim’s family for generations.

Before dinner, we exchanged gifts and the kids seemed to love the rubbery toys dad had bought. Nina was a wonderful host and also a calm mother. The kids were lovely, very well behaved, affectionate with both their parents and grandparents, giving us good night kisses without any awkwardness at all.

After dinner, during which we had discussed the Muslim duty to visit Mecca at least once in a life-time, the Haj, Iphram excitedly showed me the television channel that broadcasts 24 hours a day from Mecca of those people fulfilling this obligation.

“I will go, I promise you. It will be wonderful.”

I tried to show enthusiasm. But this didn’t diminish his.

Sarajevo, and the plaque marking the place where Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, the catalyst for the first world war

“Look at all these hotels” he said as the camera occasionally focused away from the revelers going round and round the dome. It looked a little bit like Las Vegas, but obviously this impression was left unsaid.

Both my father and I had been wondering (and hoping to see) if any slivovitz would be served, but alas, only more and more food appeared.

On my way to bed, I almost didn’t notice Nina, who usually wore jeans and a tee-shirt, kneeled by the stairs in a kind of robe with her hair covered and whispered prayers. She smiled but didn’t look at me.

The next day we drove to a town nearby, passing intermittently between Serbian and Muslim towns, in most of which the only differentiating feature was a mosque or Orthodox church. We went to a castle that overlooked the Drina river and divided Republic Srpska from Serbia proper. The town itself was bustling though jammed with cars, so we left and were taken to a quaint fish restaurant where Ibrahim insisted on paying.

We stopped in Tusla for coffee, and visited the main plaza and the place where a Serb mortar had killed 70 people in one spot. Again, Tusla was surrounded by hills, and guess who occupied the high ground? It’s impossible to fathom the mayhem and despair that would have followed such an explosion. If you witness something like that, how do you recover? And if you didn’t witness it, unless you have experienced events of human savagery, it is simply impossible to imagine how it could be, or how you would react.

We walked over to a huge swimming complex with pools of various shapes and sizes. For no apparent reason, perhaps to show off who knows, I said that I swam 4000 meters every day. Iphram was stupefied.

“Why on earth would you do that?”

I had no good answer.

Arriving at the house, I decided to go for a walk and ventured to the other side of the valley, finally getting to the top of the hill after much effort. The further up, the poorer the people seemed, and a couple of gypsy families, their yards overflowing with broken equipment and dogs, lived up pretty high. On the ridge, a sign from the Norwegian-Dutch anti-mining squad testifying to their work and also alluding to the continued danger of straying too far into the woods.

I played soccer with the kids and later dad and I sheepishly said we were going down to the village to drink some pivo, hoping that our decadence was not being judged. The bar was empty but for a few locals who looked at us quizzically but soon lost interest. Dad was unable to finish a second glass of the wine. “If I can’t finish it, it must be really bad,” was his take on it.

Once more we left the table absolutely stuffed, basically unable to move, but as we sat watching a Turkish soap opera, more snacks were prepared for us to supplement the cake and coffee already on the table in front of the television. Iphram cut up sausage and cheese, surely not for us, I thought, but it was the case.

Iphram was not particularly sanguine about Bosnia’s future.

“How you say in English, one spark and everything explodes again.”

The way Bosnia was carved up into regions at the Dayton peace talks, apparently concluded late at night after huge amounts of alcohol was consumed, left many issues unresolved and the nationalism of the politicians from all factions does not bode well for the future.

Nihad turned up mid-morning and after many hugs and sincere proclamations of keeping in touch by Facebook, we departed. It is difficult to describe the generosity and warmth of these people. There is a strong desire to drag one of these Muslim-hating fools from the west into Ibrahim´s house to show that no, they don´t sit around eating children and preparing bombs in some eternal jihad.

“I bet you ate a lot,” was Nihad´s first and accurate comment.

The route took us back through some of the countryside we had seen before, and about two hours later we arrived in Srebrenica and the site of the horrors that had taken place 23 years ago. We toured the old car factory that had served as The UN headquarters and where 20,000 people had fled to after Serbian pretentions of annihilating the male Muslim population became evident. The Dutch peacekeepers, overwhelmed and probably feeling vulnerable, turned them away, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The factory itself was eerie and one of the exhibits is simply a huge factory floor where pictures of the atrocity line the walls and disused machines rotted in the middle of the room. Across the street is the cemetery commemorating, not the best word, the 9000 victims. Endless names were engraved into marble slabs. There was a souvenir shop at the entrance to the cemetery which seemed in rather poor taste.

Dazed and confused, overwhelmed by the depravity of humanity, we stumbled out toward the town to lunch. There among the posters of candidates for the Serbian position of president (it’s a tripartite presidency) was a smiling Vladimir Putin. That can´t be a good sign.

At the restaurant, we ordered a mixed-meat plate although Nihad said that they often snuck in pork without telling the customer so he ordered goulash. The town seemed slightly dead, the main pedestrian street strewn with empty shops and the ones open hardly looked thriving. As in other Serbian towns, Nihad seemed fidgety and on edge.

The journey to Vishigrad was not without incident as the Satnat routed us through the forest on a gravel track. Eventually we turned back and descended into Vishigrad on a spectacular road that passed through a mountain gorge and had 39 tunnels of various lengths. This road, which must have cost billions to construct, was built in 1989, just before the dissolution of Yugoslavia when the country was in dire financial straits. One wonders why there was this rush to have this direct link between Belgrade and Sarajevo. Well, actually the Muslims don’t.

The scenery was breathtaking though slightly marred by the fact that the river the road followed was pretty polluted, bits of debris strewn across its entire surface the whole way down. It was a reminder of the horrendous environmental record of the Communist countries whose pursuit of the socialist paradise did not apparently include taking care of the earth that would host it.

After finally arriving in Vishigrad, we pulled into a hotel resort which honored Ivo Andric, the 1961 Nobel literature laureate. It was a huge complex with bars, restaurants and a cinema. It was also almost completely empty.

“Maybe it’s Russian mafia money laundering scheme,” Nihad suggested not without some plausibility. The receptionist tried her best to dissuade us from staying (“she should be fired”, Nihad whispered) directing us to another hotel around the block. She relented only when she realized we didn’t mind paying the fifty-dollar charge.

We were shown to a huge block of rooms, all empty except the two we would occupy. There were two cafes but we quickly moved from one when we were told that they didn’t serve alcohol there, so shifted next door.

The place really was a shrine to Ivo Andric, a huge statue to him in one corner, quotations in Cyrillic lining the walls, although as Nihad wryly pointed out that he was in fact Croatian, where they use the Roman alphabet.

Dinner was at a small restaurant. Nihad talked about how Bosnia did attract some extremist Muslim fighters from other Arab countries during the conflict.

“These guys are crazy. They came here with their Kufis and daggers and their bombs strapped to their bodies. The Serbs, even if they were in a tank or had a machine gun, they run away. Once they hear Allah Akbar, they are gone, abandoning their weapons.”

We laughed a lot about this.

Afterwards Nihad and I walked over to the 500-year-old bridge that crossed the Drina, and there was an inscription in Arabic in the middle, a testimony to the Ottoman presence there, and then went to a bar to a night cap.

Nihad opened up about his days as a violent and rebellious teenager coming of age in a war zone. He had no water or electricity for three years (I thought of him the other day when our power went out for an hour and we were outraged and also totally unprepared) and ended up in the wrong crowd.

“Physical violence, fighting and stuff, seemed so tame since people never died from a fight, but there were dying everywhere else.”

He and his crowd listened to rap music and he knew all about the 1990s rap scene. They would fight people who listened to heavy music (“with their long hair, they look like girls!”) and anyone else who crossed their path eventually.

“But I realized that I didn’t want to disappoint my parents so I stopped.” Disrespecting parents was, in Nihad’s view, the worst transgression possible. “I tell my wife, your treat my parents bad, you go.”

To get to Mostar the next day, we had to double back through Sarajevo and meander through mountains and gorges until we reached this historical town. That’s a slight exaggeration as the historical part consists of basically three very quaint streets absolutely jammed with people. One could hardly move on the bridge and dad was rebuked when he asked which side of the bridge was Croat and which was Muslim.

“Here we don’t think in those terms,” said the dour tourist agent. Ok, we’ll take your word for it!

The bridge is indeed impressive but you literally have to fight your way through thick crowds to get over it. A young man in a speedo was perched on the top of the bridge collecting money for his impending dive into the transparent water below. We didn’t wait to watch him but at lunch speculated about what it would take to have us jump off.

“Definitely if there was one of those Muslim terrorists after us shouting Allah Akbar, I would,” said Nihad.

We left dad in Mostar and headed back to Sarajevo and arrived in the late afternoon. The radio station playing in the car had the most eclectic mix of music I’ve ever heard, from hard rock to rap to traditional music to opera, quite extraordinary.

Kasey, her two sons and I went out to a special beer hall for dinner with excellent food and drink and afterwards we once again spent hours reminiscing about the people and places common to us and our history.

On the way back to Brazil, I spent the night in Madrid, arriving at the hotel at midnight, which is just about when the night scene there gets started. The streets were packed with people though the excesses of the previous night in Sarajevo curtailed my energy for doing anything exciting.

The flight from Madrid to Salvador did not start out well as I was assigned a seat in the middle of the middle row, and when I had tried to change it this wonderful airline, Air Europa, said that I’d have to pay 40 euros. I was sitting next to a middle-aged woman, who was engaged in a political conversation with two women across from her and a man sitting in front.

The woman said they would not vote in Bolsonaro, the vile right-wing idiot who is likely to be Brazil’s next president but the man was proudly one of his supporters, and I simply scowled when he said this. They then went on to pillory the left-wing agenda, saying how certain social policies had made poor people lazy and uppity, declaring quotas for minorities the most unfair thing in the world, and saying how the youth had lost their values because religion was no longer taught in schools.

I tried to phase out the conversation but it was impossible as Brazilians, especially when talking about politics, tend to speak loudly. Coming back from the bathroom, the conversation had now changed to religion, and all of them were born-agains, the man actually himself a pastor.

For the next six hours, they talked about how amazing Jesus was. The pastor, who lived in Italy, spelled out his whole life story, his youth lost to drugs, alcohol and woman.

“I had a house, I paid 250,000 euros for in cash,” (an unnecessary detail I thought), “beautiful, right on the beach. I lost that too.”

He continued, his voice more and more dramatic and quivering.

“I’m not going to cry,” he said seemingly right on the verge of doing so. Please don’t or please do, I thought in my contradictory way. “But I ended up on the streets. Do you know what it’s like to beg for money?”

He took deep gulping breaths to stem any tears. Everyone professed somberly that no, they had never had to beg.

“But after Jesus came into my life, miracles continue to happen.”

As an example: “My car caught fire, everything was destroyed except for the bible. Doesn’t that show the power of god.” I guess it did.

They ended up great friends, created a whatsup group and vowed to go to the man’s wedding next fall to a woman he had saved from drugs through Jesus. They prayed with hands adjoined as we landed since obviously it was to God’s credit that we had arrived safely.

It was a really wonderful trip, a gift to be able to spend time with dad who was a delightful companion and Kasey, a great friend, and her charmingly boisterous son Benjamin!

Arriving home is always a treat, and with all its problems, Brazil is a nice place to come back to even if it will soon be ruled by a fascist.